Welcome back to The Journey, where we track the development of prospects as they excel in junior, make the NHL, and push towards stardom. This week is the second instalment in a series on applying philosophical concepts to fantasy hockey to gain an edge on the competition.

Catch Part One, Avoiding the Ad Populum Fallacy, here.

In theory, fantasy sports are all about numbers. But emotions and psychology often play a significant role in how managers make decisions and build their teams. We understand our individual biases, preferences, and methods to some extent—I tend to tear teams completely down to the studs when taking them over, for instance, where others prefer to retool on the fly—but we also often fall prey to a range of logical fallacies and cognitive biases that operate in the background without us fully understanding their impact on our decision-making process.

This week, we are going to consider several cognitive biases and logical fallacies that commonly impact value assessments during trade negotiations. Learning to recognize and counteract your biases can help you stay in the driver's seat during back-and-forths to make solid decisions you won't regret later.

A great introduction to cognitive biases is the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which occurs when "a person's lack of knowledge and skills in a certain area causes them to overestimate their own competence. By contrast, this effect also causes those who excel in a given area to think the task is simple for everyone, and underestimate their relative abilities as well."

In other words, you probably know more about fantasy hockey than you think. Don't scuttle deals in advance just because Player A is obviously a lot better than Player B in your eyes. Don't assume everyone agrees with you, and look for moments where they don't. It might seem obvious that you would consult a few sources, apply your knowledge of league context and whatever else to better understand the stats, and then make an assessment of relative value.

If I have Nathan MacKinnon, for example, I would still trade him if the return was good enough—even though he is a star player on the Colorado Avalanche, my favourite team. I understand that the overall value of my team becomes higher by shipping him out, so out he goes.

On the flipside, a lot of poolies know much less about fantasy hockey than they think they do. Some managers still largely subscribe to the old-school approach of making decisions based on the eye test and/or season-long totals rather than analytics, for example—even if they do check and consider them to some extent.

And sometimes it's flat-out time and energy constraints. Fantasy can take up a ton of time if you let it, and in theory there is a small, cumulative advantage to be gained through constant tinkering and research—keeping tabs on the development of hundreds of prospects and pro players to better understand where the market is headed, so to speak. But a lot of people just don't have that kind of time or energy. And so there are very real imbalances in knowledge when it comes to trade negotiations.

The other thing is that not everyone plays fantasy hockey to win. That might sound ridiculous, but it's true. We also play it for fun, remember? Sometimes a team is just a random junkyard of favourite players, slowly losing trade value. Or a shiny collection of top prospects that won't be competitive for another four or five years.

So when it comes to trades, a lot of times decisions are based on something other than evidence and a desire to win, something rooted in emotion, preference, or ignorance—a cognitive bias. Here are some common reasons (other than evidence) why people make trades:

- Impatience. Giving up on prospects too quickly (not understanding Breakout Thresholds).

- Homer picks. Wanting to acquire players from favourite teams.

- Being a Slughorn. Collecting all three Hughes brothers, for instance. Or all the top goalie prospects: Wallstedt, Askarov, Wolf, and Levi.

- Personal connection. You saw a player live who gave you a "wow" moment (sniped, deked, big hit), so you want to roster them in fantasy.

- Tinker addict: trading just to get that little hit of dopamine

- Lacking/ignoring key context for production (ie. team strength, deployment, linemates, high shooting percentage, reliance on secondary assists)

- Preferring/avoiding certain "types" of players (ie. gritty, young with high potential, playmakers who don't shoot or hit)

- Bad experiences. Disliking certain players due to past disappointments (especially common with goalies and Band Aid Boys)

Now let's dig deeper into a few of these. Definitions via The Decision Lab.

Tinker Addict (Action Bias)

"The action bias describes our tendency to favour action over inaction, often to our benefit. However, there are times when we feel compelled to act, even if there's no evidence that it will lead to a better outcome than doing nothing would. Our tendency to respond with action as a default, automatic reaction, even without solid rationale to support it, has been termed the action bias."

You know that manager in your league that just sits there firing off trade after trade every single day? It's you, isn't it. Well past the point of optimizing your roster, you are now just tinkering with it. Lusting after that little hit of dopamine when that trade is accepted.

It's a real thing.

It can be handy too. If you know someone in your league who is always desperate to trade, send a few offers their way, do some back-and-forth, and then walk away if the price isn't right. Odds are there will be another offer in your inbox inside the hour—at a slightly better price. Help them with their tinker obsession by helping yourself to a stronger roster.

It's actually why Best Ball leagues can be so hilarious. Although some leagues allow trades and roster moves, Best Ball is usually a draft-and-forget format where only the stats from your team's top x players will be considered (ie. 18/25). When those teams outperform my "tinker rosters," it shows me that sometimes rosters are better when you leave them alone and just have faith in your original concept and timeline—even though it can feel like tinkering always leads to a steady upwards progression.

And even though it can be frustrating when some managers make almost no moves outside of setting their rosters, that is absolutely a valid strategy.

The Disposition Effect / Anchoring / Sunk Cost

"The disposition effect refers to our tendency to prematurely sell assets that have made financial gains, while holding on to assets that are losing money. We are driven to sell our winning investments in order to ensure a profit, but are averse to selling losing investments in hopes of turning them into gains."

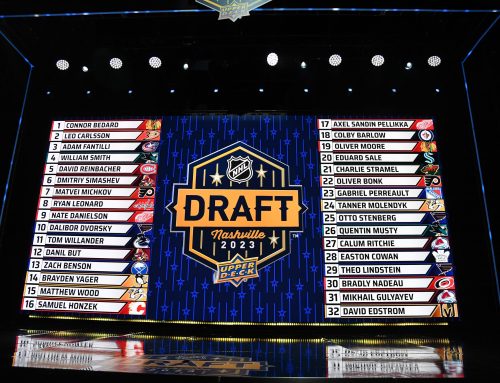

Picture this: back in 2020, you ended up drafting both Alexander Holtz (NJD) and Dawson Mercer (NJD). Holtz was the higher real-life pick (7th vs. 18th) and has more hype and pedigree. The 2021-22 campaign comes along, and Holtz ends up in the AHL while Mercer sticks with the big club and puts up a respectable 42 points in 82 games.

Then another manager offers you a package that includes a first-round pick the following year for either Holtz or Mercer.

Because you previously spent a first-round pick on Holtz versus, say, a third-rounder on Mercer, you decide to flip Mercer instead of Holtz, insisting that your investment in the former-seventh-overall pick will pay off in the future and wanting to capitalize on the value gained by Mercer.

Plus, you're probably thinking, "Holtz is better than Mercer," because that was the narrative the first time you encountered these prospects. But that might well be an "anchoring bias," which is when we rely "heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic." In fact, it might have been better to keep Mercer and flip Holtz because things changed and more information arose since you made your initial value judgement.

Then 2022-23 arrives, and Mercer puts up 56 points with the Devils versus Holtz's four. One player is firmly established in his team's core while the other is still trying to earn an extended look. This type of decision can then make you more susceptible to Sunk Cost Fallacy too: you can't sell on Holtz now because you've held him this long and haven't seen a payout.

Of course, managers often deliberately hold onto declining assets because we subscribe to the Breakout Threshold theory, which recognizes that there is inevitably a dip in value between when a player is drafted and when they hit their NHL upside after 200-400 games. It is important not to panic when a premium asset like Holtz is still working their way through the process. Even better is to let other people hold them during that time and trade for them when they are cheapest, just before they break out.

But the lesson here is to adapt to changing circumstances and be open to selling off players you thought would be foundational pieces if their value is declining, an offer is strong enough, and other players on your team are unexpectedly excelling in their stead.

Don't Blow Your Lid (Reactive Devaluation)

"Reactive devaluation refers to our tendency to disparage proposals made by another party, especially if this party is viewed as negative or antagonistic. This cognitive bias can serve as a major barrier in negotiations."

Maintaining a good reputation and open lines of communication is critical in fantasy. Trade partners are a very limited resource. Let's say you have a team in a 12-team league. Six of the managers are not very active and tend not to reply to trade offers. So realistically you have five people left to negotiate with.

Then you get a string of lopsided offers without context, while your thoughtful, balanced offers are rejected without comment. We've all been there. It can be extremely frustrating, and this behaviour is very common. It's a bit like The Boy Who Cried Wolf: it might easily get to the point that when trade offers pop up from certain managers, you decline almost out of reflex—even if one of them was actually a decent offer.

While it can be tempting to lash out and respond with something condescending or aggressive, souring the dynamic during a negotiation can both make you likely to miss out on value and mean that you have fewer dance partners for future trades.

The important part is to make sure other managers aren't reactively devaluing your offers.

You don't want to be the boy crying wolf and getting rejected by default. That means not bombarding your league mates with offers you would never remotely consider accepting yourself. Try to consider the other team's needs as if they were your own (the Golden Rule!) when constructing deals. Look for compatible positional needs or stat imbalances where a deal makes sense both ways. Send a message that explains your thinking.

You know, negotiate.

Playoff Performer (The Hot Hand Fallacy)

"The hot-hand fallacy is the tendency to believe that someone who has been successful in a task or activity is more likely to be successful again in further attempts. The hot-hand fallacy derives from the saying that athletes have "hot hands" when they repeatedly score, causing people to believe that they are on a streak and will continue to have successful outcomes."

I view the Hot Hand Fallacy as connected to the personal connection rationale mentioned earlier: let's say you were present in Vancouver for Game Two of the 2011 Stanley Cup Final against Boston. When Alex Burrows scored on a massive slapshot 11 seconds into overtime, he instantly became a legend.

Burrows had never really been a scorer dating back to his junior days—except the previous season when he scored a career-high 67 points in 82 games at the peak of the Sedin brothers era. He put up an impressive 17 points across 25 playoff games that ill-fated Cup run but then declined dramatically as a producer afterwards.

But if you experienced that moment in 2011 as a Canucks fan, you likely overinflated Burrows' value as a fantasy asset thereafter: wicked sniper, hard shot, comes up clutch in big moments, next year he'll score 40, etc. Something about being part of that moment often becomes part of the value judgement too. He did it once…he can do it again!

The other thing is that it's easy to forget how skilled every single NHL player is. I remember seeing Jamie Oleksiak pull off this bonkers goal against Nashville in his Dallas days a couple years ago, for instance, and thinking he must be capable of better offensive numbers:

But that is a shutdown defenseman who just scored a career-high 25 points in 75 games with the Kraken at age 30. It would be easy to see that play and immediately read too much into Oleksiak's offensive prowess. It was a remarkable goal, but that's not the kind of player he is.

Just because he went end-to-end once or twice, doesn't mean he'll ever score 50 points.

Thanks for reading! Follow me on Twitter @beegare for more prospect content and fantasy hockey analysis.

EDM

EDM FLA

FLA BUF

BUF DAL

DAL MIN

MIN UTA

UTA NSH

NSH VAN

VAN OTT

OTT TOR

TOR