Welcome back to The Journey, where we track the development of prospects as they excel in junior, make the NHL, and push towards stardom. This week is the second instalment in a series on applying philosophical concepts to fantasy hockey to gain an edge on the competition.

In case you missed them, check out Part One: Avoiding the Ad Populum Fallacy and Part Two: Cognitive Biases in Trade Negotiations.

In theory, fantasy sports are all about numbers. But emotions and psychology often play a significant role in how managers make decisions and build their teams. We understand our individual biases, preferences, and methods to some extent, but we also often fall prey to a range of logical fallacies and cognitive biases that operate in the background without us fully understanding their impact on our decision-making process.

This week, we are going to consider several more cognitive biases that commonly impact value assessment. Learning to recognize and counteract your biases can help you stay in the driver’s seat during back-and-forths to make solid decisions you won’t regret later.

Optimism Bias

"The Optimism Bias refers to our tendency to overestimate our likelihood of experiencing positive events and underestimate our likelihood of experiencing negative events."

As we looked at last week, not everyone plays fantasy to win. But I think it's safe to say that most of us play it for fun. When it comes to fantasy projections, it's fun to project our players for breakouts. We would love to see Connor McDavid score 150 and Alex Ovechkin to break Gretzky's record. That would be so cool!

I don't know about you, but I was pretty rattled and skeptical the first few times I saw model-based scoring projections—likely from Dom at The Athletic. I remember hearing Dom do a guest spot on Fantasy Hockey Life with Victor and Jesse a few years ago, and it felt like he (his model, I should say) was lower than them on every single player they discussed.

In retrospect, I think that impression was based on how conservative I felt the model was. It wasn't swinging for the fences, buying into hype, or sticking its neck out on a player because it believed in their raw potential. That is not to say that Victor and Jesse were doing those things either. My point is just that while the human element infuses mystery, magic, and possibility into the future, models cut through all of that to show us what is the most likely result.

Outliers happen and models are "wrong" all the time, of course, and when they are, it's easy to get excited and use these unlikely, one-time occurrences as proof that our biased assessment process was correct—and even superior—the whole time. We saw something the model couldn't. We win.

I think the gradual, general decline of gut, intuition, and the eye test in hockey can carry with it a lot of resentment in certain quarters. Many of us are reluctant to relinquish control or authority to the "machines," so if we can best AI or a computer in some way, even if it's a fluke, we will often jump to congratulate ourselves.

This phenomenon is called the Illusion of Validity: "our tendency to be overconfident in the accuracy of our judgements, specifically in our interpretations and predictions regarding a given data set." This can also apply to interpreting model-generated predictions, of course. Context is often crucial in hockey, and there are limitations on how well contextual factors—like a player and their partner welcoming their first child mid-season—can be accounted for. While models are a critical tool for accurately predicting future performance, they should never be considered exclusively or in isolation. And their results still need to be interpreted because numbers do not speak for themselves.

Yet while the Illusion of Validity can affect interpretations of all kinds, I think the Optimism Bias comes into play more often in fantasy when we avoid or discount model-generated predictions. In league chats, for instance, managers commonly throw around exaggerated assessments: "This player is garbage" or "That player will score 40 next year, book it." Any time you hear absolute language like that, you're hearing someone's Optimism Bias—or on the flip side, Pessimism Bias.

Common examples of absolute language:

- Always

- Never

- Every

- All

- No one

- Everyone

- Certain

- Impossible

- Guaranteed

No one (oops!) has certainty about the future, so you can rest assured that those who pretend to know something for sure about what will happen are wrong—even if they end up being right sometimes. It's why I take pains to constantly couch my analysis with words like "likely," "often," "probably," and "should."

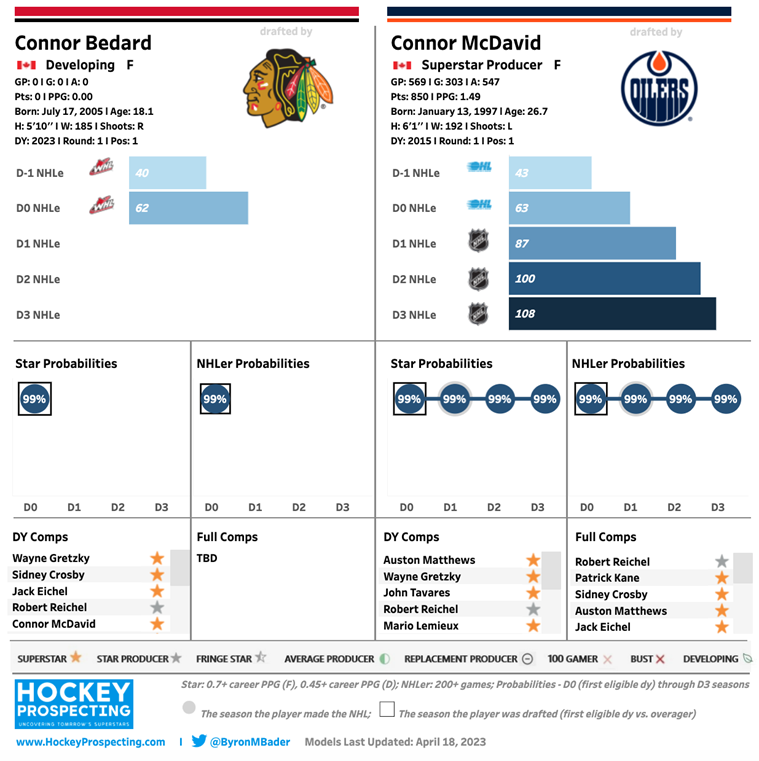

Optimism Bias is particularly common with prospects because it's all about projecting ultimate upside with developing players. At the peak of a player's career, and under ideal circumstances (ie. playing on Connor McDavid's wing all year), how much could they score? I imagine that if you ask around before the NHL draft in June, upside estimates would be inflated across the board. Connor Bedard will post McDavid numbers. Matvei Michkov will score 50 goals. Adam Fantilli will hit 100 points. Just before or after the draft is an excellent time to sell high to capitalize on the optimism of other managers.

If you survey poolies a couple years after the draft, upside estimates will almost surely be lower. The sheen has worn off, the hype has subsided, and we remember that even incredible hockey players often end up on an NHL team's fourth line.

In that dip between when players are drafted and when 80% of them hit their upside after 200-400 NHL games (as described by the Breakout Threshold Theory), the Pessimism Bias rears its head: Quinton Byfield (LAK), Alexis Lafreniere (NYR), Alexander Holtz (NJD), Kaapo Kakko (NYR), Shane Wright (SEA), Marco Rossi (MIN), Nick Robertson (TOR)—all these players are overrated potential Yakupovs in certain circles at the moment. Panic! Get what you can for them before their value falls even further! This predictable dip in value is an excellent time to buy low.

Talk to the Hand 'Cause the Face Ain't Listening (Ostrich Effect)

One reason why model-generated predictions can feel so conservative is that they avoid the Ostrich Effect, a cognitive bias "that describes how people often avoid negative information, including feedback that could help them monitor their goal progress." Models need to be correctly programmed, of course, and the people behind key sites like Evolving Hockey, Hockey Prospecting, HockeyViz, etc are constantly making adjustments and attempting to hone their formulas to better reflect and predict reality.

But generally speaking, statistical models will not neglect to consider particular data points that darken a player's outlook. Fantasy managers, however, are much more prone to biases and can twist themselves into contortions to explain away certain aspects that don't fit into their preferred view of a player.

Let's say I'm really high on Andrei Kuzmenko (VAN), for example. He just scored 38 goals as an overage rookie. Next year, when he's more established and comfortable in the league, he'll score 40+ right? Optimistically, sure. But realistically, there are several red flags with his profile that actually suggest regression. He scored on 27% of his shots, for instance, which led the league by over 5% (!) amongst players with at least 50 games. His high PDO (1027) also indicates that he was disproportionately lucky in 2022-23, as does his high secondary assist rate of 60%.

A model will take those factors into account and skew lower than 38 goals in its prediction; but a die-hard Vancouver fan might stick their head in the sand (like an ostrich), call all of that nonsense for this or that reason, and take the over on 40—because it's fun. It's more magical to believe that Kuzmenko will hit 40 than that he won't. Or that Bedard will exceed a point-per-game in 2023-24 versus scoring, say, 65 points. But is it realistic?

If you are playing fantasy to win, you want realistic so you can make informed decisions and accumulate more stats than your competitors. If you're playing for fun, however, maybe you prefer the magic.

Player Comparables (Representativeness Heuristic)

A related, equally controversial point is about how we throw around comparables in fantasy when discussing prospect potential and trajectories. In Philosophy, this is known as the Representativeness Heuristic, "a mental shortcut that we use when estimating probabilities. When we're trying to assess how likely a certain event is, we often make our decision by assessing how similar it is to an existing mental prototype."

Some fantasy experts are extremely reluctant to bring up comparables for this reason. There are so many factors that make players unique and explain their particular impact on the game—so many that it is basically a fool's errand to try to make comparisons.

To return to Bedard one more time, he is being cast as a generational player in the same tier as Connor McDavid and Sidney Crosby. But each of these three players are incredibly distinct, even if their raw era-adjusted statistics end up looking similar at the end of their respective careers. That comparison only really tells us that Bedard has a chance to ascend to a rare echelon of hockey production; it does not tell us anything about how he might get there.

The problem with using comparables is that they are a shortcut. It is hard to hold a ton of complexity in our minds all the time, so saying Player A = Player B is very convenient. When we try to remember our general value assessment of a given player, we can think of their established comparable to get a ballpark.

This shortcut is not necessarily a problem; we use comparables throughout the Dobber Prospect Report, for instance. As with all cognitive biases, however, the trick is to recognize what our brains are doing and respond accordingly—in this case, with skepticism about the accuracy of comparables even if they are a useful touchstone.

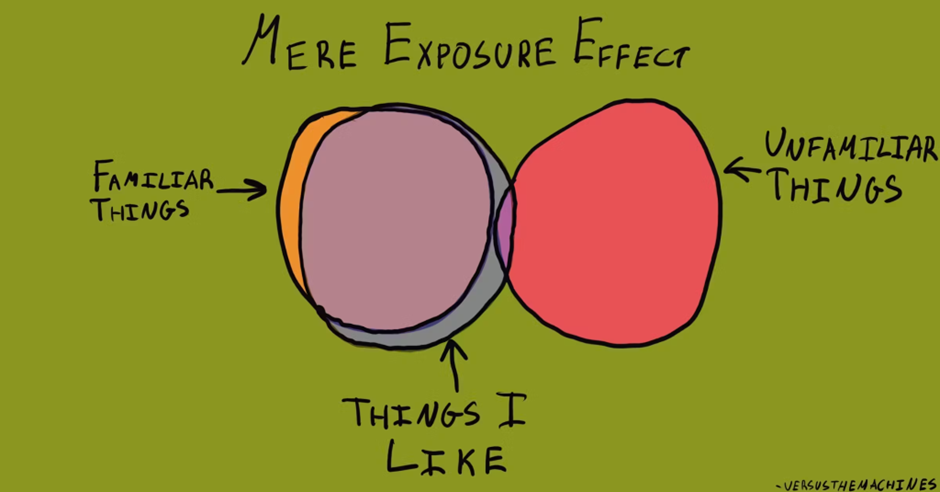

I Don't Know That Player (Ambiguity Effect & Mere Exposure Effect)

I want to conclude by mentioning two final, interrelated biases that can also cloud our assessment of player value: Ambiguity Effect, which describes "how we tend to avoid options that we consider to be ambiguous or to be missing information," and Mere Exposure Effect, which is "our tendency to develop preferences for things simply because we are familiar with them."

I was recently in a trade negotiation with a manager in one of my leagues who had shown a willingness to move farm picks fairly cheaply for established prospects close to seeing NHL time. I had stocked up on a number of prospects like that for the purpose of trading, so I figured we could make something work. After scanning the 32 players on my farm roster, however, he said he didn't recognize any of them. And that was the end of our negotiation.

He didn't know my players—had not been exposed to them—and didn't care to take the time to. They were ambiguous to him, so he devalued them. He figured that if they weren't on any of the top prospect rankings yet, they weren't worth his time. Fair enough!

The lesson I took away from this interaction is that if I'm stocking prospects with the primary intention of flipping them, I need to do a better job at reading my audience.

I might know that Marat Khusnutdinov (MIN) and Andrei Kovalenko (COL), for instance, are likely to cross over to North America at the end of the 2023-24 and earn roles in their respective teams' top sixes right off the hop. Or believe that Quentin Musty (SJS) is one of the higher-upside forwards from the 2023 draft. Or that lesser-known defenders like Artyom Duda (ARI, 59%), Mike Benning (FLA, 49%), and Michael Buchinger (STL, 42%) all have very high star potential ratings according to Hockey Prospecting. But if my fellow managers don't know that, they probably won't value them accordingly—even if I try to share my perspective during negotiations.

That is the impact of the Ambiguity and Mere Exposure Effects, which also explain why many managers prefer to collect players from their favourite teams: they already know them.

***

Thanks for reading! Follow me on Twitter @beegare for more prospect content and fantasy hockey analysis.

EDM

EDM FLA

FLA CHI

CHI ANA

ANA CGY

CGY